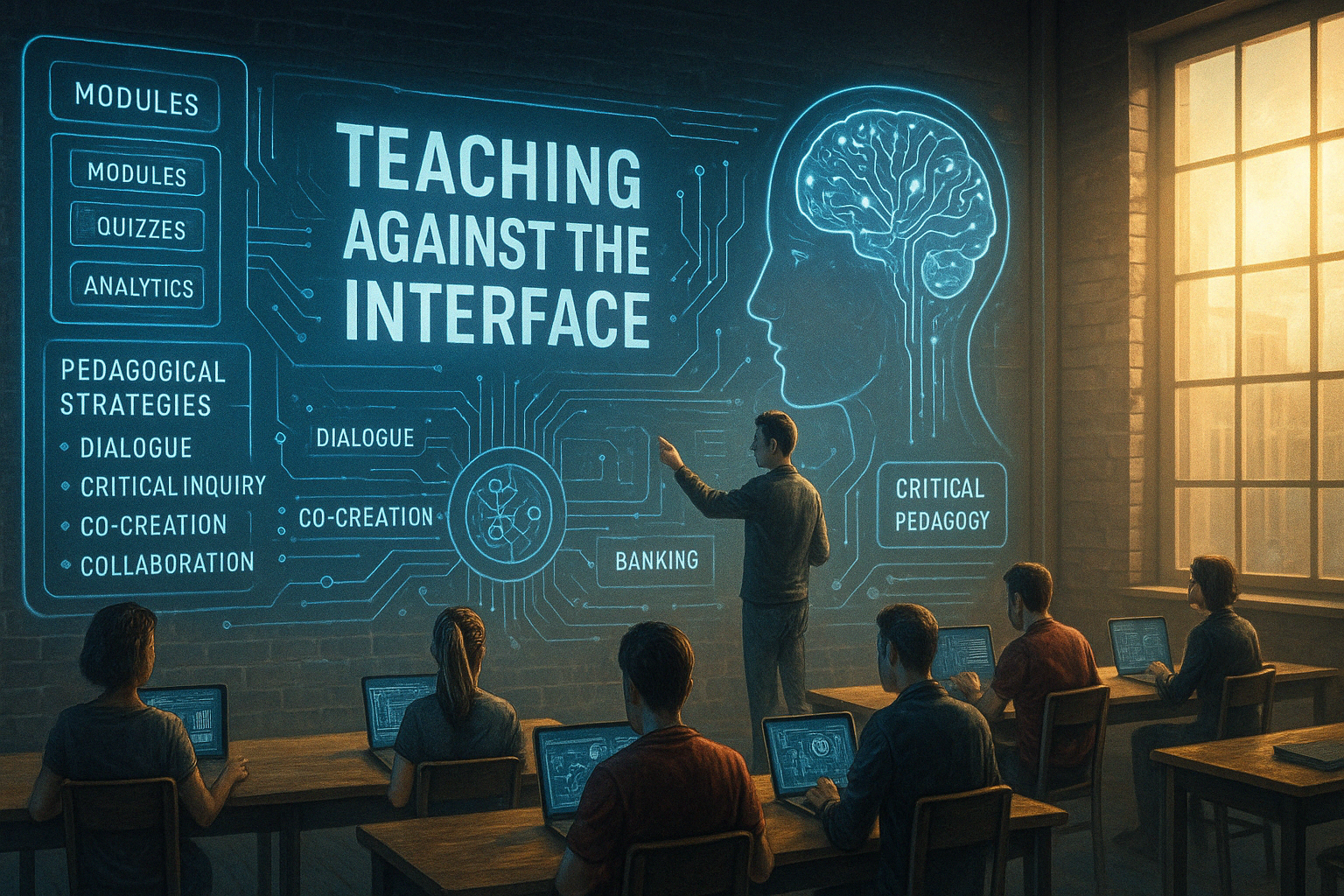

Teaching Against the Interface: Reclaiming Pedagogy in Platformed Learning

The university I work at is currently transitioning from Blackboard to Canvas. At one level, this is a straightforward migration - out with the old VLE, in with the new. Canvas offers a cleaner interface, more integrations, and promises greater user-friendliness. But at another level, something more subtle and consequential is happening. We are not simply changing tools. We are reconfiguring the architecture of our courses, the rhythms of our teaching, and the boundaries of our pedagogical imagination.

This post explores what it means to “teach against the interface” - to resist the flattening effect of platformed education and reclaim a more expansive, critical, and dialogic pedagogy. Drawing on the tradition of Critical Pedagogy and the work of Paulo Freire, I argue that educators must be wary of how digital platforms constrain our choices and, more importantly, our sense of what teaching and learning can be.

Platformed Learning and the Default Pedagogy

Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs) like Blackboard and Canvas are more than neutral containers for content. They are platforms, and like all platforms, they come with assumptions about what education is and how it should happen. The term platformed learning captures this shift towards education delivered, managed, and analysed through systems optimised for consistency, scalability, and control (van Dijck et al., 2018).

In Canvas, for example, the logic of the platform is embedded in its defaults: preconfigured module structures, linear progress tracking, automated quizzes, and analytics dashboards. These features encourage certain patterns of use - chunk content, test recall, track progress, measure engagement. The platform rewards compliance with these patterns through convenience and visibility.

Educational technologies are never neutral. The tools we use to teach shape what we believe is teachable. The platform itself can become a kind of hidden curriculum, guiding educators toward a narrow model of instruction focused on delivery and compliance rather than inquiry and transformation.

The Risk of Pedagogical Flattening

When educators adapt their pedagogy to fit the tool, rather than adapting the tool to fit their pedagogy, something is lost. This is particularly evident during transitions like the one we’re currently undergoing. Templates are used to migrate course content quickly, but with them come inherited structures and settings that often go unexamined.

We risk what I call pedagogical flattening - a loss of complexity, messiness, and ambiguity in favour of tidy progression bars and clickable milestones. The learning journey becomes a checklist. The student becomes a user.

Freire (1996) critiqued the “banking model” of education, where knowledge is deposited into passive learners. Platformed learning, left unchecked, risks reinforcing this model through its design. When pedagogy becomes subordinate to workflow, when interface design dictates interaction, we must ask: who is teaching whom?

Towards a Critical Digital Pedagogy

Critical Pedagogy, as articulated by Freire and expanded by others, offers a powerful lens through which to resist platform determinism. Central to this tradition is the belief that education should be dialogic, emancipatory, and situated in the lived experiences of learners (Giroux, 2011; hooks, 1994).

In practical terms, this means looking at how we use Canvas - or any VLE - with a critical eye. How might we subvert the default configurations to reintroduce uncertainty, dialogue, and co-creation?

Some possibilities:

- Reclaim the discussion forum from superficial Q&A to spaces for genuine inquiry, using open prompts and student moderation.

- Restructure modules to allow multiple, non-linear pathways through content—encouraging exploration over consumption.

- Use collaborative tools like shared documents, wikis, and annotation platforms that decentralise authority.

- Avoid surveillance features such as detailed learner analytics unless used for dialogue and support, not discipline.

These are small acts, but they amount to what Jesse Stommel (2014) calls pedagogical disobedience: intentional departures from standard practice that reassert the centrality of human relationships in teaching.

Educators as Designers and Disruptors

One of the more insidious aspects of platformed learning is how it can render educators passive. We are “users” of the system, not designers of it. Yet teaching is fundamentally an act of design - of crafting experiences, encounters, and provocations that enable learning.

To teach against the interface is to reclaim this role. It is to make conscious decisions about when to follow the platform’s lead and when to diverge. It is to see every checkbox, every rubric, every page layout as a choice - not a given.

At its core, this is about professional and political agency. Educators must refuse to be “content managers” and insist on being pedagogical thinkers. This is especially important in distance learning contexts, where the technology can easily overshadow the pedagogy.

Institutional Change Requires Pedagogical Dialogue

Transitions between VLEs are often framed as technical projects. But they are pedagogical interventions whether we name them as such or not. Institutions must therefore create space for educators to interrogate - not just adopt - the tools they are given.

This means:

- Creating communities of practice where educators share and reflect on divergent uses of the platform.

- Recognising the labour involved in resisting defaults and building more intentional courses.

- Supporting experimentation and even failure, as signs of a living pedagogical culture.

A Freirean approach calls for dialogue not just with students, but among colleagues. As bell hooks (1994) writes, “education as the practice of freedom” begins with talking honestly about what we are doing, why we are doing it, and how it might be otherwise.

Conclusion: Teaching as a Political Act

When universities change platforms, they often talk about cost, support, and student satisfaction. Rarely do we talk about pedagogy. Rarer still is any mention of politics. But teaching is a political act - especially when mediated by digital platforms.

To teach against the interface is not to reject Canvas or Blackboard wholesale, but to approach them critically. To see their limitations. To resist their defaults. And to find, in the small choices of design and interaction, space for something freer, messier, and more human.

Let us not only migrate content - we must migrate consciousness. From the passive to the active. From the managed to the intentional. From the default to the possible.

References

- Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the Oppressed New revised ed. London: Penguin.

- Giroux, H. A. (2011). On Critical Pedagogy. London: Bloomsbury.

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

- Stommel, J. (2014). Critical Digital Pedagogy: A Definition. Hybrid Pedagogy. Available at https://hybridpedagogy.org/critical-digital-pedagogy-definition/ (Accessed: 17 April 2025).

- van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & de Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.